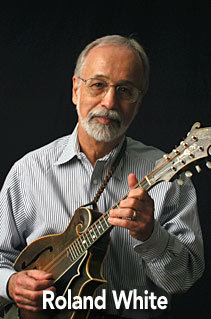

Roland White – Mandolin

It is a warm spring evening in Nashville. Inside the world famous Station Inn a crowd that was waiting in line even before the club’s doors opened at 7 p.m. is anxiously awaiting an evening with the Nashville Bluegrass Band (NBB). The small listening room is packed with NBB faithful. Returning from Los Angeles, where their latest album, Unleashed, won the Grammy for album of the year only a week earlier, the band’s members are in high spirits, mixing with the members of the crowd, laughing, joking and telling stories. Then, shortly after nine, the band opens its high energy set. Halfway through it, Roland White steps up to the microphone for his first vocal solo, Bill Monroe’s “Toy Heart.” For White, who turns in his usual solid performance, this evening is the latest triumph in a journey that began many years before and many miles away.

It is a warm spring evening in Nashville. Inside the world famous Station Inn a crowd that was waiting in line even before the club’s doors opened at 7 p.m. is anxiously awaiting an evening with the Nashville Bluegrass Band (NBB). The small listening room is packed with NBB faithful. Returning from Los Angeles, where their latest album, Unleashed, won the Grammy for album of the year only a week earlier, the band’s members are in high spirits, mixing with the members of the crowd, laughing, joking and telling stories. Then, shortly after nine, the band opens its high energy set. Halfway through it, Roland White steps up to the microphone for his first vocal solo, Bill Monroe’s “Toy Heart.” For White, who turns in his usual solid performance, this evening is the latest triumph in a journey that began many years before and many miles away.

In fact, he still remembers clearly how it began. Barely eight, Roland, the eldest of the White children was helping his mother in the kitchen as they listened to a country radio station. As one song faded into the next, White asked her one question after another about the singers he heard. As they spoke, he told her that he, too, hoped to sing on the radio one day. Practice, she told her son, and you might be able to earn your living just like the folks on the radio.

The moment was a revelation for young Roland. “When I heard that I thought, ‘Man, that’s what I want to do.’ And, it seemed like the more I thought about it, the more I wanted to do it.” For a boy with these intentions, there may not have been a better place to be than the White household in those days. Growing up in the rural state of Maine with few outside distractions, White was surrounded by his father’s siblings, 16 in all, many of whom were musicians. There were always instruments around and plenty of people to play them. And almost every week, somebody was buying a new 78 rpm record to add to the Whites’ diverse collection.

Often, White’s father and uncles met there to sing and play. At first, White and his sister, Joanne, would join in the singing. But before long, White had a guitar in his hands and was trying to mimic the sounds his dad made on the instrument.

Focused on his dream, White organized “band” rehearsals each night with his own younger brothers, Eric and Clarence. Though the younger White boys were initially more interested in playing outdoors, White, with the backing of his parents, persisted until the practices became a regular part of each day.

White says his father always supported his musical ambitions. “If he was doing something around the house I would hang out with him and ask to help. He’d say, ‘well, I’d rather you be working on your instrument.'”

Though he started on the flattop, it wasn’t long before the future Blue Grass Boy had a $2.50 “tater bug” mandolin in his hands. He still remembers how comfortable it was to play the smaller instrument initially while Eric played tenor banjo and Clarence the guitar, and Joanne sang and sometimes played bass. To start, says White, the three of them would play old time country songs they learned from their father and uncles. “We just played what we knew,” he says.

Throughout the early 1950s, the White children were learning all the songs they could as fast as they were able. About once a month the boys would play in local Grange Halls, and they performed at family gatherings and for household guests. By the time their father moved the family to Burbank, California, for a new job, the children were ready to take their careers to the next level.

Only a month after arriving in California, the White children entered and won a talent contest on a local radio station. Then, the boys auditioned at an area television station for a new show that was looking for “kid” acts. They were hired on the spot as the “Country Boys,” this time without Joanne, who decided not to continue.

California also opened other new worlds for White and his siblings. It was there that he received his first exposure to Big Mon. Playing a $25 F-style Kalamazoo brand instrument by this time, White says one of his uncles told him about a mandolin player on the Grand Ole Opry named Bill Monroe who was “pretty good, pretty quick.” That led him to a local music store where he ordered, at random, a 45 rpm version of Monroe’s “Pike County Breakdown.”

White was a little frustrated upon first hearing Monroe. “I thought, ‘This is neat, but this is really fast.’ We never played it like that back then. But it was interesting to try and break it down, which was almost impossible at first.”

Not long after he received the record, White saw Monroe for the first time on television. “It was Christmas Eve of 1956 on a show called Town Hall Party, I was watching him and I had my mandolin in hand. In fact, that’s how I learned to do mandolin chords. It was a real eye opener to see how was holding his hands,” says White. Around this time the brothers first met banjo player Billy Ray Latham who, with Roland and Clarence, would ultimately form the nucleus of the Kentucky Colonels. “When we met him, we invited him over to the house and that was it, there was our bluegrass band.”

Over the next few years the band played constantly and made regular appearances at a Hollywood folk music club known as the Ash Grove. Then, in 1960, Roger Bush took over the bass duties from Eric and the Colonels lineup was complete. The band was then joined by Leroy McNees on Dobro, while Bobby Slone and Scott Stoneman would sometimes add their fiddling to the mix.

In 1963, after Roland returned from a two-year stint in the Army, the Colonels toured the eastern half of the country, playing clubs and coffeehouses. The next year they returned to the East and made a well-received appearance at the Newport Folk Festival in July, where an extremely-nervous Clarence was invited to a guitar workshop hosted by Doc Watson. “It was probably the biggest crowd we had ever seen,” says White. In that same year the band recorded its critically acclaimed album, Appalachian Swing, recently reissued on Rounder Records. Ironically for an album that has become a centerpiece in many bluegrass instrumentalists’ collections, White says Appalachian Swing was recorded without vocals as a way to cut costs.

As the folk boom died down in the mid-’60s, the Colonels found it harder to get bluegrass gigs. And, by 1966, Clarence, who had begun playing more electric guitar, left to do studio work, which eventually led to his joining the Byrds. Roland, meanwhile, had taken up electric bass and was playing country music in Southern California’s lounges to help make ends meet. In 1967, White made his way back to bluegrass when Bill Monroe was touring California. Lamar Grier, then Monroe’s banjo player, told White the Blue Grass Boys needed a guitar player to replace Doug Green, who was returning to college. “I knew I could do what he needed, so I asked him for the job and he hired me,” says White. The job with Monroe lasted for the better part of two years until White signed on as mandolin player with Lester Flatt’s newly formed Nashville Grass. He stayed with Flatt four years until deciding to reunite with brother Clarence in 1973. Billed the New Kentucky Colonels, the brothers performed on the East and West coasts, made a tour of Europe, then went to California to prepare to record an album. But just as the venture began it was over. In July of 1973, as Roland and Clarence were loading their equipment into the car after a gig, the pair was struck by a car. Clarence was killed and Roland sustained minor injuries. There were many things the pair had intended to do, says White. “Clarence wanted to try lots of different things; some electric, some acoustic,” says White.

After the accident, White returned home to Nashville to regroup when he got a call from Roger Bush and Alan Munde, who had formed the successful Country Gazette.

“They needed a guitar player and asked if I was interested. Well, that was just the thing I needed. I had been really looking forward to working with Clarence again, we had plans and then I had nothing. So, I took the job,” he says.

White fondly remembers the 13 years he spent as the Gazette’s guitar player then mandolinist. “The fun part was working with the people who were in the band…Alan, Roger, Byron Berline, Kenny Wirtz, Joe Carr. They were great. Creativity [in this band] was happening with new arrangements, new songs, new venues.”

Since 1989, White has had his current gig as the mandolin player for the NBB, referred to by some as the “state-of-the-art” bluegrass band. “Though we are bluegrass, I sometimes think of us as an acoustic country band. We’ve played all kinds of songs that didn’t come to us as bluegrass songs at all. If anyone tells me: ‘I’ve got a bluegrass song for you,’ I don’t even want to hear it, because it probably won’t be any good. The bluegrass songs have been written…by Bill Monroe, Lester Flatt and others. Those songs have been done, they’re like the old jazz standards, and they’re great and I still like to listen to them.”

While he still listens to the old Monroe and Flatt and Scruggs albums, White confesses a real love of jazz and says he is just as apt to have the recordings of Herb Ellis, the Modern Jazz Quartet or Freddie Green in his compact disc player. Someday, he hopes to learn it well enough to perform and record it.

Over the years, all of these influences and experiences have helped White to develop a unique style. His playing is simple, uncluttered and relaxed with a clock-like sense of timing. And, White feels that playing has found a real home with the NBB. “I don’t know who else I would want to work with. I played with these guys around town a long time before they formed the band and when they did I thought, ‘This is the coolest thing since Monroe and Flatt and Scruggs played together.'”

White offers nothing but praise for each of his fellow bandmates. On fiddler Stuart Duncan: “Every time we play he will do something that will make me just want to drop my pick. He’s just so remarkable.” On guitarist and vocalist Pat Enright: “He’s a great rhythm guitar player. He’s just wonderful, he never does anything that doesn’t work. It’s straightforward and simple and no one knows how to do it except for Pat. It’s hard to do.”

“Gene Libbea,” says White, “is the kind of bass player that nobody has in bluegrass. He has played all kinds of music. I really like what he does; he’s an eye opener and other people need to listen to what he’s doing. And Alan O’Bryant is a hellacious banjo picker and singer. I don’t know why he doesn’t get any awards for his work, he sings the heck out of anything he does.”

With a lineup that appears secure into the foreseeable future, and the second Grammy award under their belts, Roland and his colleagues hope to continue to spread the bluegrass gospel far and wide. The key to gaining widespread acceptance of the music, says White, is television. Just as television brought him his first glimpse of Monroe, White believes it has the potential to create millions of new fans. “Everybody’s got a tv. If there was one good bluegrass concert on a week, you’d see lots more people buying the music. That’s what happened with country music.”

Country singer Marty Stuart, who has known White since the days when the two played in Lester Flatt’s band, recently wrote this of his friend: “For those of us who love bluegrass music, it’s always been the same. It’s understood that Bill Monroe is the Father of it all…but time has a way of crawling along and taking the responsibility for the future to other souls. As long as I know that Roland has a voice in the inner circle, I know that everything’s going to be all right concerning the tradition and future of bluegrass.”

For more information about Roland, visit: RolandWhite.com